SPL Crescendo duo Microphone Preamplifier Review

Gorgeously clean gain for your microphones

High-quality preamps that can capture all the nuances and subtleties of classical guitar are not as common as one might think, as most designs introduce too much noise and colour. When I came across the SPL Crescendo duo microphone preamp last year, I was intrigued by its specially designed 120-volt technology, which promises a particularly neutral, dynamic and low-distortion sound. I immediately contacted SPL and they sent me a demo unit to test.

Sound Performance Lab

SPL (Sound Performance Lab) is a German company that has been manufacturing professional audio equipment for about 40 years. SPL is known for its innovative designs and audio solutions of the highest quality. Their preamps, converters and headphone amplifiers are used in recording studios for music and film worldwide. Common features of all SPL products are the impressive build quality and enormous size.

SPL Crescendo duo Microphone Preamp

The Crescendo

The Crescendo 120-volt rail preamp design was introduced with the original 8-channel unit; the duo, as the name implies, is the stereo version, ideal for recording classical guitar in situations where good enough is not enough.

One of the ftings that sets the SPL Crescendo duo apart is its large knobs and tactile switches. Each channel provides from +18 dB to +70 dB of gain, which can be independently increased or decreased by 10 dB with a switchable output control. In this way, the rest of the chain can be supplied with an optimal level. The total output can reach up to 80 dB, which is more than sufficient for even the weakest ribbon microphones.

The physical VU meters for level adjustment leave a remarkable impression and can lower the displayed level by 10 dB if necessary. A high-pass filter of 6 dB per octave at 120 Hz is quite useful, although I would prefer it to be switchable for greater versatility. Nonetheless, every aspect of the Crescendo duo has been carefully thought out.

SPL Crescendo duo - tactile switches and VU meters

Four times more voltage

The 120 V technology operates at +/- 60 V. To handle such a high voltage, SPL has developed special proprietary operational amplifiers (SUPRA) that can operate at a such high voltages, as this would destroy conventional components and operational amplifiers.

How it sounds

After using the Crescendo duo in my recording setup for a couple of months, I am happy to report that it exceeded my expectations. The SPL has a very clean and transparent sound, which is essential when recording classical guitars. Many preamps introduce colouration and distortion that can detract from the subtleties and nuances of the recording. The result can sometimes be pleasant, but it strays far from the original sound and is usually not what we are looking for when trying to capture luthier-grade guitars and world-class guitarists. It's worth noting that unlike other clean preamps, the Crescendo is not a bit shrill, but has an overall smooth and warm sound.

A high-end setup & ‘The Music of the Impressionists’

I used the SPL Crescendo duo to record my latest album, The Music of the Impressionists, which contains a wealth of tonal colours, sustained tones, great dynamic differences, and silences. I used my beloved Essense guitar, handcrafted by Angela Waltner in Berlin, and in conjunction with a pair of Gefell M 950 microphones (review coming soon), another marvel of German engineering, and the RME ADI-2 Pro FS for the analogue-to-digital conversion, the Crescendo captured every detail brilliantly.

Listen to ‘The Music of the Impressionists’ on Spotify:

Comparisons

SPL Crescendo duo vs AEA TRP2

The Crescendo duo is similar in many ways to the AEA TRP2, another highly regarded preamp that I have used for several years. Both units are known for their clean and transparent sound, and both have low self-noise and high maximum gain. However, the Crescendo has a bit more refinement, smoothness and realism in its sound. The sonic benefits, additional features, and fantastic build quality of the preamp are worth the price difference. However, I will also keep the AEA TRP2 for some field recordings, as it is easier to transport.

Some thoughts on microphone preamps

Most audio interfaces have adequate preamps for most applications and users. So unless every other aspect of your recording chain is well thought out, searching for microphone preamps is a futile endeavour. The differences between clean mic preamps are only subtle but can become important when combined with other competent equipment and production skills. If you are confident in your setup and all you are missing is a good mic preamp, I'd suggest forgoing cheap deals and saving up until you can afford a high-end preamp like the Crescendo duo.

The Coda

The SPL Crescendo duo microphone preamp is one of the best options for recording classical guitar. It is a well-designed and sophisticated device that is capable of producing excellent recordings and is made to last a lifetime.

Best Reverb Plugin for Classical Guitar

Classical guitar performance is meant to be experienced in a natural space; the player, the guitar, the room, and the audience summon an ensemble and create a unique contract. As recordists, we aspire to capture such magical moments, but we don't always have the luxury to operate in fantastic-sounding spaces. As producers, we sometimes record in our homes or bland-sounding studios, in such occasions, the use of artificial reverb is unavoidable.

For a decade or so, I've been a happy user of 2CAudio's reverb plugins, Breeze at first and then Aether, as you can read in my post for the Three Essential Plugins for Classical Guitar. However, I recently got a MacBook Air M2 (review coming soon), and these plugins are not yet compatible with Apple's processors. Thus, although I'm still pretty satisfied with the results I got from both Aether and Breeze, I have to find their replacement.

Note: As I learned after starting this test, Logic can run x86-x64 plugins natively and without having to setup Rosetta. Possibly with a hit on the CPU, but this should only become appartent on more heavy projects that solo classical guitar recordings. This fact make the need to find new plugins a but less imminent.

After an initial market research, I downloaded trial versions of all plugins that caught my eye and are compatible with apple's silicon. Testing software with so many variables can be intensive, therefore I spent enough time with each plugin to understand its interface and try to make it work for my taste and needs.

The reverbs I tested this time:

Neunaber WET Reverberator

Strymon BigSky

Universal Audio Lexicon 224 Digital Reverb (Spark Native)

Universal Audio Pure Plate Reverb (Spark Native)

FLUX IRCAM Verb v3

Apple Chromaverb

RELAB RX480

RELAB RX480 Essentials

FabFilter Pro-R FLUX IRCAM Verb v3

LiquidSonics Seventh Heaven

TC Electronic VSS4 HD Native (Non-compatible with Apple ARM Processors)

2CAudio Aether (Non-compatible with Apple ARM Processors)

2CAudio Breeze2 (Non-compatible with Apple ARM Processors)

My final assessment of the usefulness of these plugins is asserted not only on sound quality, ιntuitiveness and adjustability play a minor but meaningful role.

My least favourite reverb plugins

Neunaber WET Reverberator

No matter how much I tried, I couldn't make the Neunaber WET Reverberator Plugin sound decent enough for my uses. I wanted to like the sound, as the WET pedal, that the algorithm originates, is quite popular among electric and flamenco guitarists. In all settings, there is always some chorusing on the reverb tail that I couldn't remove, and the space doesn't sound realistic, natural or with a desirable sound signature.

The price of the WET Reverberator Plugin is reasonable, but considering that there are a few plugins at a similar price (especially during sales), besides the decent sounding free plugins included with most major DAWs, I cannot recomended it even for those on a tight budget.

Strymon BigSky

Another plugin ported recently from a pedal with an almost cult-like following is the Strymon BigSky Plugin. I was looking forward to testing it, however the experience was underwhelming. Not only the sound quality of the Room, Plate and Hall algorithms was not on par with the other reverbs of my test, but the tweakability was also pretty limited. Perhaps the other algorithms included could justify the high praise and price, but for classical guitar, the sounds were not convincing enough. Thus, another hard pass unless you are looking for shimmer reverbs for your classical guitar.

Apple ChromaVerb

The last of the three not-good-enough reverb plugins is Apple’s ChromaVerb, which is included in Logic's vast plugin collection. The UI is much more intuitive than the "pedal" plugins, and getting a usable sound was not that hard. As expected, the ambience created by the ChromaVerb pales in comparison to the most sophisticated reverbs of the test; it lacks finesse and sounds more like an effect than a realistic space. But given that this is a free option, the results were better than expected.

The good but not-for-me

LiquidSonics Seventh Heaven

Another plugin that seems to be loved by many producers is the LiquidSonics Seventh Heaven. LiquidSonics claims to reproduce the algorithms of the acclaimed Bricasti M7. I have never used the M7 in person, so I cannot confirm or deny this. What I can back up is that the Seventh Heaven has a rich and refined sound, and I can see why it is so popular. The interface is pretty modern and intuitive, I was able to get a sound I liked right away. After comparing it to some of the other plugins though, I concluded that it sounds a bit too polished and generic for my taste. It is worth noting that the Seventh Heaven is the only convolution-based reverb of the test.

Moving on, a reverb plugin that will satisfy those who want extreme control over how the space sounds is the FLUX IRCAM Verb v3. The Verb v3 creates the most realistic-sounding room recreation of the bunch, and could be perfect for film production or other uses that realism and accuracy are desired. In addition, the control the UI provides is pretty phenomenal. I needed some time to get to know how every parameter affects the sound, but after a while, the somewhat uncommon layout made total sense, and I was pleased by how much control the Flux plugin offers. Soundwise, the IRCAM reverb lucks a bit of musicality and elegance for solo classical instruments.

FLUX IRCAM Verb v3

A utility reverb plugin

One of my favourite plugin developers is FabFilter. I really like how powerful their various plugins are, love the clean and pristine sound quality, and appreciate the modern and intuitive UI. I own their Mastering bundle and use it almost every day.

I downloaded the trial version of the Pro-R when it was released a few years ago and did enjoy the user interface and sound, but not enough to change the 2CAudio reverbs I have been using almost forever. This time, I got to play more with the Pro-R and even used it in the production of my latest release: 'Will Have Been'. It is a very intuitive and capable reverb plugin, not my favourite sounding of the bunch but very useful and easy to use. So, I'm debating getting it now or waiting for a sale, but FabFilter's Pro-R will definitely find its place in my collection.

FabFilter Pro-R

Rent or own

Universal Audio Lexicon 224

A reverb plugin I was happy to see released in native format - without requiring the expensive dongle that is called Apollo - is Universal Audio's Lexicon 224 Digital Reverb. Universal Audio has the resources to create some great plugins, but some of the hype comes from the fact that they were only available through their DSP-powered interfaces. That was perhaps necessary a decade ago, but computers today are so powerful that this business model makes little to no sense. With the release of Spark Native, Universal Audio seems to have realised that.

Universal Audio Pure Plate

The Universal Audio Lexicon 224 Digital Reverb sounds musical and manages not to get in a way. Besides, lots of attention has been given on the UI, which looks beautiful but is a bit limited. The Pure Plate reverb sounded perhaps even more musical, albeit less natural for solo classical guitar.

I liked both reverbs from Universal Audio, but if there is one thing I hate more than USB dongles is the subscription model for software - an argument against using Adobe apps as well. Now, $149,99 a year for all the Spark Native plugins is not so bad. But, considering that I don't have any use for any of the other plugins, I decided to cancel my subscription at the end of the trial period and reevaluate later.

Early reflection goodness

When I first got into recording, personal computers were not powerful enough, and native plugin offerings were pretty limited. For that, I used to own a TC Electronic Powercore unit and loved the TC VSS4 algorithm. The Powercore was much of a hustle later on for me to keep using it, and native plugins became capable enough, so I parted ways with it. TC Electronic released the VSS4 HD Native plugin, and although it is not compatible with apple silicon yet, including it in the comparisons can only be constructive.

TC Electronic VSS4 HD

The VSS4 HD sounds pristine and lush, with some of the most realistic early reflections. It makes any recording sound somewhat more three-dimensional. Oher algorithms may sound more pleasing for longer reverbs, but the VSS4 HD is hard to beat for short realistic reverbs.

Vintage vibes

RELAB RX480 v4

One of the best-sounding reverbs of the bunch is the RELAB RX480 Dual-Engine V4. It is supposed to be sample-accurate dual engine recreation of the legendary Lexicon 480L. I cannot confirm or deny the claim as I never had the pleasure to listen one in person. The RX480 is truly stunning with its plush, thick sound. A more modern UI could make the RX480 more straightfoward, as the LARC-type graphic control would make more sense to those with experience with the original Lexicon units, but I could live with that. It is much more impreesive than the UAD 224 Reverb and sounds more pleasing to my ears. The Random Hall algorithm especially is impeccable.

Moreover, RELAB has a lighter version, the RX480 Essentials, which packs the same basic 480L sound with a less overwhelming UI and at a burgain price for what you get.

The familiar

2CAudio Aether

I purchased the 2CAudio Breeze several years ago, then moved on to the Aether. I'm using both plugins it tandem sometimes; the Breeze for a more natural space and Aether for a thicker sound. Both plugins are exceptional, with first-rate sound quality and offer plenty of control. I was so pleased with this combination that I stopped looking for other reverbs. I somehow also missed trying the Breeze2 when it got released.

As it is obvious, I'm used to the sound of these plugins. I downloaded a trial version of Breeze2 to conclude this comparison. Both 2CAudio plugins sound admirable, with the Aether being the most versatile, especially for those who are also into sound design. But I was particularly surprised by the Breeze2. The placement of the solo classical guitar in space is very realistic and offers lots of depth. The Breeze2 sounds lush without sounding as much as an effect or too sterile as some of the other plugins.

2CAudio Breez2

Although it is not yet compatible with the Apple ARM chips, and perhaps there never will be. Given that I already had the first version, the update to the Breeze2 was inexpensive for me, so I didn't give a second though. Unfortunatelly, due a dispute at 2CAudio, the future of the company is currently uncertain. So, I cannot recommend either one, at least for now.

Some thoughts on convolution reverb

I've tried convolution reverbs in the past and had determined that they don't work for me, but I thought that this time might be different perhaps. In addition to Apple's Space Designer, I downloaded the Inspired Acoustics Inspirata Silver and HOFA IQ Reverb v2. As much as I wanted to like them, I never got them to blend well with the dry tone. Admittingly, impulse respneses sound very natural and realistic, but It always sounds like a cross-fade of room ambience and classical guitar layers than an instrument in a room. Furthermore, the IRs tend to get a bit weird whenever I am pushing them. I understand that the results rely on the specific IRs, but I get satisfying results with algorithmic reverbs to investigate convolution reverbs further at this time.

Conclusions

If who don't have a problem with subscriptions and might have uses for the other UAD plugins, the Spark Native is hard to beat. For a versatile reverb with a clean but superb sound, the FabFilter Pro-R ticks all the boxes. Lastly, for vintagey charachter and thicker reverbs, the RELAB plugins are outstanding.

For me, the Breeze2 will replace the original Breeze for realistic but musical sounding spaces, and the LX480 will replace the Aether for characterful reverbs. And, I’ll keep an open spot for the FabFilter Pro-R.

Three Ways to Improve your Recording Space Without Spending Any Money

Let’s talk about the room - Part I

When we think about improving our recorded sound, we usually think about upgrades in gear; we lust for new microphones, interfaces, guitars, etc. We don't want to buy new things; we absolutely need them. Sometimes, we even postpone recording altogether until we have the budget for purchasing said gear.

The harsh truth that we sometimes don't want to admit is that spending more money on gear will not fix fundamental issues. Getting a good sound in the room before we hit record is essential, as essentially, this is the sound that our microphones hear and our interfaces capture. Fix it in the mix does not apply with classical guitar recordings wherein room and performer are equally exposed.

Having used all sorts of gear in all possible situations, I rank all the elements of the recording chain in this order: guitarist, guitar, room, microphones, engineer, playback system, post-production skills, preamps, converters, cables. Leaving everything else aside, in this article, I examine a few ways to get the best out of a typical residential room without spending any money.

Disclaimer - room treatment can be approached from a more technical standpoint which I plan to discuss here in the future. Contrarily to what the vendors of acoustic panels will say, household items can be used as a pragmatic alternative, even more so considering the singular commitment of a classical guitar recording space.

First. The sitting position.

Sometimes out of being lazy or just practical, we set up everything as is and keep the room as we would normally use it, especially if we don't have a dedicated music room. Considering the degree that the room affects the recorded sound, searching for a suitable sitting position should not be overlooked.

Before all else, when I enter a new space for a session, I try to figure out the best sounding position in the room. This habit applies both for on-location to home recordings and even concerts to some degree. I'm not getting into detail about on-location recordings and big spaces now, as this goes beyond the purpose of this text.

I have assembled a few guidelines to help you search for the perfect sitting position in your room but keep in mind that every room has unique sound properties.

First of all, you want to avoid sitting close to the walls and most definitely steer clear of the corners; the build-up of low frequencies and the early reflections will cloud the direct sound of the guitar. Also, the centre of the room is far from an ideal sitting position, especially in a room with parallel walls.

In an ordinary rectangular room, if possible, you'd want to sit alongside the long walls about three-fourths to two-thirds of the length of the room. In addition, I find that sitting a bit off-centre and facing the front wall at a slight angle towards the longest distance produces the best results; this modest break of symmetry helps.

Nonetheless, you need to experiment with your space as every room is different. Perhaps asking someone else to play your guitar in a couple of different positions and try to listen is not a bad idea. If this is not possible, pay attention to the sound while you play; singing can also assist you in identifying the room modes. Moreover, you'll need to record yourself in various spots and listen critically; recording the same piece can make comparisons less ambiguous.

What you are looking for is the most balanced sound; play all notes of your guitar in sequence as well as your favourite piece, and if it gets boomy or any frequency stands out a lot, try a few different angles or move a little. If the room is untreated, which probably is, the result will not be outstanding, but in any case, it is worth finding the position where standing waves are not encouraged, then acoustic treatment can be employed.

Second. Other uses for your books.

Speaking of acoustic treatment, this goes without saying, at least to some extent. But, as our rooms usually serve (at least) a dual purpose, a playing/recording space along with a listening/production room, some compromises have to be made. Critical listening requires a controlled environment, while what makes a good room for recording acoustic instruments can be partially subjective.

I have recorded in all sorts of situations, from big halls with a vast reverberation to heavily treated studios with no ambience at all as well as everything in between, thus I have concluded that I genuinely don't enjoy playing in an acoustically dead room. Even if the captured sound in such a controlled room is somewhat easier to handle, the performance and feel of the music always take a big hit. Clever microphone placement and good post-production skills can make almost any room sound acceptable, contrary there is nothing we can do to improve an uninspiring performance.

Thankfully, the classical guitar is not the loudest instrument around, with a lot of its energy residing is in the mids and highs, so it is not impossible to minimize the small room sound signature. Whilst is more convenient to record at home, on-location recording is never out of the question; I could always visit one of the exceptional sounding halls in Berlin or elsewhere when absolute sound is required. It is also refreshing to work on other rooms.

Wherein large rooms we have to deal with diffuse sound fields, which pose their challenges anyway, small rooms suffer from early reflections and resonances associated with standing waves. Dealing with the low frequencies below 300Hz is rather troublesome as wavelengths are large and spread omnidirectionally, while higher frequencies behave more like rays.

The key here is to use a combination of diffusion and absorption strategically. Since broadband diffusers and absorbers can get expensive fast and need to be quite thick to have any effect at the low-mid and low frequencies, there is a free alternative you can use effectively: books.

Books placed on shelves create an uneven surface, forming some sort of diffuser from which sound waves are reflected in different directions. Moreover, paper absorbs some of the sound energy, so a bookshelf works in addition as an absorber.

Gather your books and build a bookshelf on the front-facing wall (in the typical control room, the front wall is considered the one where the monitors are placed, here I use the term to indicate the wall you face when you play your guitar). Use different book sizes and thicknesses, and experiment on the relative depths; this bookshelf will absorb and scatter the sound in the room while maintaining some liveliness.

Admittingly, a bookshelf won't do much to the lower frequencies, and its properties will be somewhat random. However, you probably have plenty of books in your household already, and a bookshelf is more eye-pleasing. Plus, they are nice to read from time to time.

Third. The floor.

Since the guitar hangs in closer proximity to the floor than any other reflective surface around you, bouncing frequencies would cloud the direct sound. Also, the somewhat low ceilings and small dimensions of residential rooms dictate for closer and lower microphone positioning that say a concert hall, thus heightening the problem.

To tame the room ambience to a certain degree, place a rug between your guitar and the microphones. Avoid covering the whole room with a carpet, but rather use a small to medium-sized one.

Experiment with a few different sizes and thicknesses until you find what works in your space. Your goal is to allow the microphones to capture a cleaner sound while maintaining the room ambience. The absorption will only be effective at the high frequencies. I use a woollen rug of medium thickness that extends from just under my seating position to a bit further than the position of the microphone stand.

Closing

With the advancement in technology over the last twenty years, quality recording equipment has become pretty affordable consequently capturing compelling recordings at home is no longer impossible. However, we should not forget that the microphones capture the sound of our guitars in our rooms. So, be intentional and learn trust your ears.

Best Type of Microphone for Recording the Classical Guitar

One of the most usual questions I get asked is which microphone is the best for capturing the classical guitar, but as with all deep questions in life, I'm afraid there is no simple answer. Our guitars, nails as well as playing techniques differ vastly. Besides, our rooms have unique properties, and of course, our tastes vary. Another decisive factor is our listening environments, but that's a subject for another day.

I've written on Classical Guitar Tones extensively about the different microphones, brands and models. If you have been here for a while, you've seen me test all sorts of microphones, entry-level to high-end. In this article, I take a step back and present my thoughts on the different types of microphones, their strengths and weaknesses. Plus some words on the different polar patterns.

On being passive

Ribbon microphones have a relatively simple design with no active circuitry and use a thin metal ribbon suspended in a magnetic field. Most ribbon designs hear sound bi-directionally and produce natural and complex recordings. They have the reputation of being fragile and need careful handling and storage.

Dynamic microphones are similar to ribbons as both capture sound by magnetic induction. In contrast, they are very robust, resistant to moisture, and have low sensitivity. In practice, they offer no real asset in classical guitar recordings as their advantages benefit mainly on-stage use and capturing of loud sources.

For the most part, I don't get along well with ribbon or dynamic microphones, mainly because of their sensitivity or lack of. I often play soft passages or employ silence in my music, and with passive microphones, one has to crank the gain on the preamps to get sufficient levels, resulting in unwanted noise. After all, the classical guitar is a soft and delicate instrument, and no matter which preamps you use, it is impossible to get noiseless classical guitar recordings with passive microphones.

Ribbon microphones are also quite forgiving to the various mechanical "non-musical" noises, such as nail and fretting sounds. And this is why some people love them, especially on harsher and louder instruments and a less subtle repertoire. But, I find the response of most but the finest ribbon microphones, principally with the thinnest ribbons (some Royer, AEA, and Samar makes come to mind), quite sluggish.

Phantom power required

Nowadays, there are a plethora of active ribbon microphones, purposed for capturing softer sources and being less dependent on the preamp choice. These tend to work better with classical guitar. Yet, even high-end active ribbon microphones are far from being noiseless. I understand that for some people noise is a nonissue, but for me, it is a distracting element. I like deep blacks and hate when the softer parts or rests are being washed away by preamp hiss.

Also, the figure-eight polar pattern found in most ribbons makes them less than ideal for many recording situations. They do work nicely as a side microphone in an M/S stereo array.

Capacitors move the (recording) world

Condenser microphones require a power source to function and generally produce a high-quality audio signal mainly due to the small mass of the capsule. They can capture on tape utmost detail, sometimes even too much of it, and are the most used transducers in recording sessions and concert halls.

Most of the classic designs have been either tube or transformer equipped condensers, but with the dominance of digital recording, transformerless solid-state condensers have increasingly gained popularity in classical recordings for their additional clarity and lower self-noise.

Size matters

Condenser microphones are categorized by the size of their diaphragm and come in two main types: small-diaphragm, like most Schoeps' and the Neumann KM184, and large-diaphragm, like the Neumann U87 and AKG C414.

So, which one is better for the classical guitar, you may ask? Not so fast. Again, the answer is not straightforward.

Let's talk first about their differences.

Small diaphragm condensers are usually more accurate, with a faster transient response and superior off-axis response. They are also smaller and lighter, so they are easier to carry, besides being visually unobtrusive. The latter is a decisive factor in why SDCs dominate the concert world.

Paying audiences generally don't enjoy seeing a stage the musicians surrounded by several dozens of microphones and bulky heavy-duty stands to support them. Neumann, Schoeps and DPA provide small-diaphragm condenser systems with every possible polar response and mounting option a classical sound engineer might on location.

Polar patterns say more than you think

The downsides of using SDC's on a classical guitar, especially at home, are only a few but nontrivial. Small-diaphragm condensers are tuned for specific roles. Directional microphones are either purposed for close spots on soloists, used in combination with a stereo array at some distance, or for the main pickup and thus are tuned to compensate for the high-end frequency loss that occurs. The result, when used inappropriately, is either a poor low-end response or hyperrealistic recordings with exaggerated high-end. In other words, they can easily sound thin and harsh.

On the other hand, SDCs with an omnidirectional response (the real microphones), especially those that have been tuned for the free field, offer an optimal response at both ends of the spectrum. Additionally, they provide greater flexibility in positioning owing to the absence of proximity side-effects but become a challenge to use in non-treated rooms that universally suffer from early reflections and standing waves.

Microphones with wide- or sub-cardioid polar characteristics come to close the gap, with a better low-end response than their cardioid cousins, some room rejection, and sometimes less pronounced high-end. Unfortunately, small-diaphragm cardioids with such polar patterns are rare, and except for the bargain Line Audio CM3 / CM4, they are always on the expensive side.

So, where does the good old large-diaphragm condenser fit?

Generally speaking, LDC's suffer from a pronounced proximity effect, transient smoothing and suboptimal off-axis colouration. In addition, they require sturdier stands, are more difficult to position due to their size and weight, and can be quite visually intrusive in videos.

All these intricacies cannot be good, right? Moreover, excellent sounding large-diaphragm condensers suitable for the classical guitar are quite rare and expensive, as most LDC's are targeted for vocal pickup.

Any advantages?

As I wrote above, noise on a recording can be distracting. The smaller the size of the capsule, the greater the self-noise of condensers. Tube and transformer-based microphones are also subject to higher noise levels. Therefore, transformerless large-diaphragm condensers have lower noise to signal ratios, with several Gefell, Austrian Audio, and Neumann models reaching nonexistent self-noise figures.

Likewise, many universal studio LDC's grant additional flexibility, as they bring multiple polar patterns, removing the need to own or carry multiple microphones or capsules on a session. With a modern microphone, like the excellent and most versatile Austrian Audio OC818, you can not only choose on the fly between any possible polar pattern, but you can also do it long after the recording has been completed.

Here is my recording of Debussy’s Prelude VIII. Recorded on location with a pair of Austrian Audio OC818s.

Let's proceed to checkout.

One can make a good recording with any decent microphone, some experimentation and post-production skills to boot. There are no excuses for bad recordings in 2022.

On a budget, neither ribbon nor large-diaphragm condenser microphones of decent quality can be found as cheaper offerings are made either for a vintage vibe or vocalists in mind. Line Audio's small-diaphragm condensers are the undenied kings of the entry-level recording setup.

When searching for a high-end classical guitar recording setup to capture a world-class guitarist with a magnificent guitar in an excellent sounding room, a pair of exceptional and well-positioned omnidirectional or somewhat directional condenser microphones is hard to beat. DPA, Gefell, Austrian Audio and several high-end Neumann condensers come to mind. In such a scenario, the size of the diaphragm is incidental. With less ideal conditions, even high-end SDC's on a solo classical guitar, be it directional or not, can expose flaws and produce unattractive recordings.

To conclude, in most situations I favour large-diaphragm condenser microphones for their inherent sound qualities and noiseless behaviour. First-class LDCs can produce a luxurious recording and provide a pleasant listening experience. I also like how they look on videos; unapologetic, proud and predominant, almost commanding. With that said, the realism that some of the best SDCs treat the listener when every element is exemplary can be breathtaking.

Perhaps it is more advantageous to bring together small- and large-diaphragm condensers in an elaborate three- or four-microphone array.

Stereo Microphone Techniques for the Classical Guitar

Stereo recording is the technique that involves two microphones that due to the captures the time differences of sound waves coming from a source, which gives depth and space to the recording. Similar to how our ears and brains record and process sound.

The Classical Guitar, albeit small, is an instrument with a complex sound and subtle peculiarities; and as such, it sounds better when is captured in stereo. Various stereo recording techniques have been developed since the early 1940s; each with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

If you ask, which is the best microphone technique for capturing the classical guitar in stereo, I'm afraid that the answer is not so simple. Room size, acoustics, the instrument, and the purpose of the recording, play a significant role; as well as our individual preferences.

In this article, I describe the most common stereo techniques from the point of you of a classical guitar recordist. I discuss their strengths and weaknesses, as well as prefered uses for each setup.

Note: This article is a work in progress; X/Y, M/S, and NOS setups will be added in the following weeks.

Spaced Pair Setups

AB Stereo

AB Stereo Array

The AB Stereo recording technique is based on a pair of spaced Directional or Omnidirectional microphones and provides in a pleasing and accurate capture with useful spatial information.

For home recordings, AB Stereo is one of the best options as it is easy to implement and get a consistent sound. A pair of Cardioids is usually preferred as they can successfully attenuate the room ambience.

Omnidirectional microphones capture the true low-end of the instrument though and have no proximity effect. You can position them closer to the source in a small room, or further away if the acoustics allow.

Application

Use a (minimum) distance of 20cm between the microphones for the most natural result. You can use a greater width, as the distance from the instrument increases, for a wider capture. I prefer a width between 30 and 40cm, for small/medium rooms, and up to 60cm for large halls.

If you position the AB Setup close to the guitar, you should avoid placing any microphone opposite to the soundhole, to prevent boominess. A microphone on each side of the soundhole will give the most balanced sound, off-axis towards the fretboard for more articulation or opposite of the bridge for a fuller sound.

The microphones are most commonly parallel to each other; but, since most microphones show a degree high-end directivity, we can fine-tune their response by angling them on the horizontal plane. If you aim them slightly outwards, you can attenuate some of the unpleasing mechanical noises of the guitar (fretting noises, squeaking, nails, etc.) You can also angle them slightly inwards to reject some of the room reflections.

The directional information as captured by an AB Stereo is not as accurate as of the coincident and near-coincident setups. This attribute can be an advantage if the performer moves a lot and assists in avoiding off-balanced results. I hardly ever pan the channels hard left and right, to preserve the integrity of the central image of the classical guitar.

The biggest drawback of the AB Stereo is its leaser compatibility with MONO playback (for example, a youtube video played on a smartphone); as a result, comb-filtering may be introduced.

Suitable Polar Patterns: Omni, Cardioid

Advantages

Easy implementation

Pleasing sound

Useful spatial information

Control of room ambience

Disadvantages

Playback in MONO may introduce comb filtering

Not the most accurate directional information

And here is a real-world example of the use of AB Stereo on Classical Guitar in a professional setting. I used a pair of Austrian Audio OC818 microphones set in a Custom Polar Pattern that combines the best of Cardioid and Omni qualities. The spacing of the microphones is 26cm. The goal was to capture the pure tone of my Angela Walter guitar together with the incredible sounding main hall of the Musikbrauerei in Berlin.

Near Coincident Setups

ORTF Stereo Technique

ORTF Stereo Array

Developed in the 1960s by the Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française, the ORTF is a stereo microphone configuration that with the use of two near coincident Cardioid microphones mimics the human ears.

The spacing of 17cm and 110° angle emulate respectively the distance between our ears and the shadow effect of the human head. The result is a realistic depiction of the sound field, both in directional and spatial areas, as well as a reasonable Mono compatibility.

Application

A pair of first-order Cardioid condensers is required for a proper ORTS, 17cm between the capsules and 110° angle. Other directional patterns can be used with respective changes in the width; for example, Schoeps suggests a distance of 21cm for the MK22 Open Cardioid capsules. You can also adjust slightly both the spacing and angle for the best sound.

The most critical aspect of ORTF is to balance the direct and diffuse sounds, as there is not much you can do in post-production afterwards. As always a minimum distance of 50cm is advised to avoid boominess, but I have had better results with a distance of 80cm to 110cm. At greater distances, a low-end boost might be required to compensate for the loss of low-end of directional microphones.

The ORTF main application is for large-scale sources, like orchestras and choirs. If positioned in a close distance, you might experience loss of focus with a perceived hole in the centre.

Consequently, depending on the room acoustics, the ORTF stereo array may be proved problematic in a home recording setting. As you might either have to place the microphones further away from the instrument, capturing the unattractive ambience of a small room, or suffer a smeary sound if you position the array closer.

Suitable Polar Patterns: Cardioid

Advantages

Realistic stereo field

Reasonable Mono compatibility

Disadvantages

Perceived Hole in the middle and loss of focus if positioned close to the source

Coda

Distance

The distance of the microphones to the source depends purely on the room size, the instrument, and the setup. As a rule of thumb, keep it smaller than that of the microphones to the front and side-walls. But never closer than 50cm.

Directional microphones have a sweet spot where the proximity effect eliminates, and the low-end frequency response becomes linear. If the microphones are not in the ideal position, you might need to apply a Low-Shelf EQ (boost or cut). Omnidirectional microphones have a better low-end response regardless of the distance but capture sound from all directions. So, be careful not to end up with an overly roomy recording.

Height

Most classical guitarists angle their guitars somewhat upwards to push the sound further back (and fill a concert hall). Correspondingly, the height of the microphones depends mainly on the distance to the guitar. The closer they are to the instrument the lower they need to be. If you place the microphones further away from the guitar, they need to be higher to retain definition and accuracy.

The sound travels as an impulse rather than a beam though, so there is some room for experimentation. If you prefer a fuller sound, you can position the microphones slightly lower. Contrarily, you can increase the clarity if you put the microphones higher. Use your ears and taste.

Vertical Angle

You can also exploit microphone angles in the vertical plane; you can increase clarity if they are on-axis with the top of the guitar, or aim them at a higher point to attenuate some of the high-end and undesired mechanical noises from the strings and nails.

About the Samples

I recorded all the examples with a pair of Austrian Audio OC818. I choose the OC818 for their clear sound, low self-noise, and multi-pattern options. The height of the microphones was 103cm (centre of the capsule), and the distance from the guitar was 90cm.

The signal chain was an AEA TRP2 Microphone Preamp into an RME ADI-2 Pro FS ADDA Converter.

I didn't provide samples in other distances as they would only give cues about my room and instrument, without adding value to you.

Closing thoughts

Recording the classical guitar is a meticulous exercise. Regardless, if you want to record your next album, a video for youtube, or your performances to share with your friends, it is an utterly satisfying process. It is also a reason to practice harder and become a better guitarist.

Before your press "rec" for the first take, allow some time to find the best position, height, and angle. It can be a matter of having an excellent recording or rendering the whole session useless. Small changes in this context may have dramatic results; they act as a physical equalizer.

There have been quite a few times that I had to re-record a performance because of a poor decision, or having to rely on heavy equalization to make it acceptable when it was (almost) impossible (or expensive) to record again at the same location.

I hope that this guide will be helpful in your recording adventures in the quest of capturing the best qualities of your instrument and room.

6 Common Mistakes When Recording the Classical Guitar at Home, Part II

Part II - Post Processing

Professional sounding classical guitar at home is not a fantasy anymore or at least achieving a recording quality that is not embarrassing to share. Affordable audio interfaces, preamps and microphones have flooded the market these last decades, with increasing performance and processing power. Rooms, recording techniques and mixing are holding us back.

In the first part on the 6 Common Mistakes When Recording the Classical Guitar at Home, I tried to encourage you to try out different microphone positions and to study your room acoustics.

The second part focuses on some of the common mistakes of beginner classical guitar recordists on utilizing a proper signal chain and achieving satisfactory results in post-processing.

Mistake no.1 - Improper gain staging

AEA TRP2 Gain Knobs

The fear of clipping the converters leads some amateur recordists to use too little gain, resulting in recordings that are low in level. Without adequate signal-to-noise rations, these recordings will become noisy when any attempt is made to bring them at a normal level during mixing or playback. Contrarily, recording too “hot” will possibly clip the converters and can introduce nasty sonic artifacts to the audio. In either case, the recording will suffer from a limited dynamic range and high noise; attributes that we don't usually associate high-quality classical guitar recordings.

My advice is to aim between -6dB to -12dB as a maximum peak level (not average), per channel. Therefore, when you are happy with the placing and distance of your microphones, do a couple of test recordings, play as loud as you would normally do and set the gain levels accordingly. If you set the levels correctly, you will have a healthy and strong signal, but even if you (or another guitarist you are recording) eventually get carried away during the performance, you still have enough headroom to avoid digital clipping.

Mistake no.2 - Unrealistic panning

Classical guitar is a small instrument, radiating sound from a definite point in space. One of the worst choices you can make if you record in stereo (which you should) is to use a too wide panning. Regardless of if the listener is an audiophile type, sitting on his couch perfectly balanced in front of a pair of top-tier speakers, or a regular person listening to music with earbuds. A hard-panned left and right guitar will sound unnaturally wide and cloudy.

Proper panning of Stereo AB channels

A realistic classical guitar recording is one that creates a phantom image of the instrument right in the middle of the speakers, but with some space around it. Such recordings can remove the playback medium and transport the listener in the room with the player.

In typical AB Stereo scenarios, I pan one channel at 3 o'clock and the other at 9 o'clock. I fine-tune the panning according to the polar pattern of the microphones, how apart they are set, and the distance from the guitar.

Mistake no.3 - Limiting dynamics

Classical guitar is not the most dynamic instrument, and if anything, we should strive to capture as much dynamic range as possible (it starts from the player, so we should also prioritise dynamics in performance). Compressors, on the other hand, are designed to do just the opposite; minimize the dynamic information of an audio track by limiting the loudest notes and boosting the softest signal.

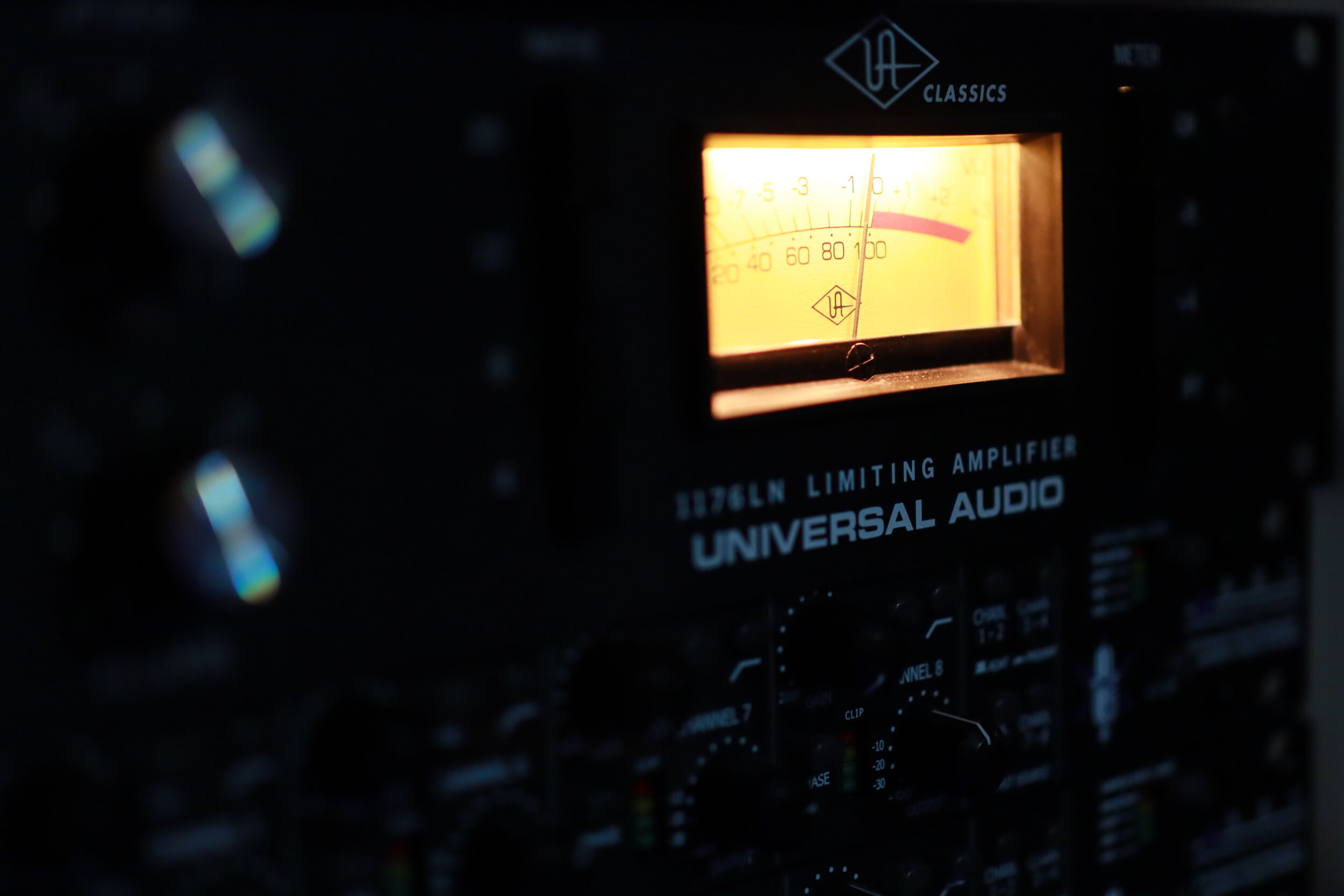

The classic Universal Audio limiting amplifier

Compressors do make the initial playback sound more exciting and powerful… for a few seconds, but in my opinion, it never pays back. Some of the problems that are introduced with the use of compressors in solo classical guitar recordings are squeezed dynamics, increased noise level and altered instrument tone.

Cross-genre guitarists employ compressors more often, as they learn that they can be invaluable in a dense mix. But I haven't found any use for dynamic limiting in a properly captured classical guitar recording.

Therefore, unless you have to deal with issues of the room or improper microphone positioning, don't use compressors on classical guitar recordings.

Mistake no. 4 - Being afraid of using filters

High-pass filter’s switch on an Austrian Audio OC18

Many microphones feature high-pass filters, the most common are 40Hz, 80Hz and 120Hz; the same is true for some dedicated outboard preamps. But many beginner recordists are afraid to take advantage of them. The truth is that in the context of the classical guitar, not much musical information is presented at the low-end frequencies. Most of what is below around 80Hz is unwanted room rumble and weird resonances; therefore by attenuating them, we end up with a cleaner recording. Capturing what is essential and leaving out the rest.

As low frequencies can have a lot of energy, it is preferable to cut undesirable low-end before the signal hits the converters, if possible. This tactic allows us to set the gain and levels appropriately and leads to better signal-to-noise ratios. But even if your microphones or preamps don't have any filters, you can still apply a high-pass filter in your DAW to remove non-essential information.

I also like to use a low-pass filter to remove high-end information that is inaudible, so that my audio consists of only the frequencies I can hear. A gentle roll-off of the low (below 50Hz) and high frequencies (above 18000Hz) is a good starting point. An EQ plugin with these basic filters is the first plugin I load on every track. You can read more on the article Three Most Essential Plugins for the Classical Guitar.

Mistake no.5 - Not learning how to use an equalizer

Other than the low- and high-end unwanted information that we can simply remove with the appropriate filters, undesirable resonances can occur in the audible range as well. These can be caused by the imperfect rooms that we are recording in, our instruments or our technique. Obnoxious resonances can and will distract the listener.

Learning how to use an equalizer to detect and attenuate or eliminate such issues will make the listening experience much more pleasurable.

The best way to identify an offending frequency is by using your ears. I know that this doesn't sound like great advice, but keep reading. When you detect something that you don't like, add a bell-shaped point on your EQ with an extreme boost and search through the suspected range, like dialling in an analogue radio.

Once you find the irritating frequency, the sound should be quite disturbing at that point, apply a notch or a generous cut with a narrow Q. Toy around with the Q value to find the sweet spot; a setting that makes the problematic sound disappear but lets the rest of the audio unaffected.

FabFilter Pro-Q 3 with HP & LP Filters, a narrow Q Cut and a High Shelf Boost

Another use for an EQ is to change the overall balance of the recording. Sometimes you'd prefer a slightly fuller recording, or there is just a bit too much low-end. Perhaps the treble is a bit piercing, or you'd like to add some more clarity and articulation. Making gentle adjustments like these are generally uncomplicated with the use of Low or High Shelf adjustments. Just a couple of dB's can make a drastic difference to the evenness and impact of our music.

Just be careful not to overdo it, and always compare your mixes to your favourite recordings.

Finally, you can also use an equalizer to completely change the sound of an instrument and shape it to your liking. But if you've been diligent with the microphone positioning, and you like your guitar sound, you won't have to.

Mistake no.6 - Too much reverb

Placing the music into an artificial hall is a necessary lie

As I write on the Three Most Essential Plugins for the Classical Guitar article, nothing will affect the listener more than the physical space that the music takes place.

When we record at home, most rooms are not interesting enough, and so we need to enhance their sound with artificial reverb. But it is easy to overuse reverb, as it makes everything sound "better". Or so we think when we first enter the home recording world.

Most beginner recordists tend to choose a random church preset without any consideration to requirements of the music, tempo and other aesthetic choices. The result is a flood of unnatural and unattractive recordings which instead of sounding realistic or enchanted, they feel cheap.

Learn how the Time, Size and EQ settings found on your reverb plugin of choice to fine-tune the sound the ambience. Then turn down the Mix a little bit more than what you think it should be. Lastly, compare your efforts to commercial recordings (not that those are not guilty of overusing fake church algorithms).

Closing thoughts

Proper mixing can turn a decent recording into a great one

I hope that this article will make you more conscious of your post-processing choices. I need to write dedicated articles for the use of equalizers and reverb as there is a ton of things to discuss.

I know that many guitarists don't want to fuzz around with plugins, but proper audio processing can transform a recording. Mixing is an art in itself; a necessary evil that can turn a decent recording to a great one. Quality classical guitar recordings are important for your audience and benefit the classical guitar community as a whole. Thus, it's definitely worth the time and effort to learn how to mix your audio. Alternatively, you may search for someone else to do that for you.

Tip: You don't have to mix every track from scratch; after all, you probably record the same instrument with the same microphone technique and in the same room all the time. Create a template in your DAW with your basic panning, filter and reverb settings. You'll still have to tweak around a bit, as not every piece favours the same settings, nor every day is the same. Templates are great time savers.

A Three-Microphone Setup for Recording Classical Guitar

An M/S Stereo alternative.

Classical Guitar is a complex and rich sounding instrument; as such, it sounds better when is recorded with at least two microphones. A statement that you must have read several times already if you hang out at this site. Some engineers argue though that guitar is a relatively small instrument which tends to sound too "wide" when recorded with the most conventional stereo techniques; thus sounding unrealistic in playback.

Neumann TLM 193 and TLM 170 in M/S Stereo Configuration

Mid/Side stereo, which I discuss in my Three M/S Stereo Setups for the Classical Guitar article, is usually praised for its truthful representation of the classical guitar. The elimination of phasing problems and the flexibility it offers during mixing are additional important advantages, however, it is not immune to potential issues. Namely, the collapse of the room information in mono reproduction, and the inability to hear the resulted-combined sound without some processing to the channels (or the use of an M/S matrix). Lastly, symmetrical Figure-8 microphones, required for the "Side" channels, with a balanced response are generally expensive.

Alternatively, the combination of a "Mono" microphone placed at close-proximity and a "Stereo Pair" at some distance, shares some similar advantages without the drawbacks of M/S Stereo. Hence the Three-Microphone Setup is an appropriate option for capturing the subtleties of the classical guitar.

Purpose in position

Austrian Audio OC18 - A Large Diaphragm Cardioid Condenser

The "Mono" microphone is positioned close to the instrument (at about 50cm, although some could go as close as 30cm) to capture a full-bodied sound. I recommend a large-diaphragm condenser with a smooth treble response for this position; as not only it will capture the fullest sound, but the slower transient response of the large capsule will also give a less analytic, more relaxed response.

The "Stereo Pair" is placed a little further away to capture the sound of the room. A pair of small-diaphragm condensers is ideal here due to the better off-axis response and can be either Omni or Cardioid patterns depending on the acoustics. The actual distance depends mainly on the room; accordingly, as the distance increases, the height of the microphones should be increased as well. The distant pair brings to the mix crucial depth, space and some high-end articulation.

Decisions; Player vs Audience

Another way to see the three-microphone setup is as a fine compromise between the intimacy of what the player hears and the somewhat distant experience of an audience member.

During mixing, the three channels can be balanced to the desired sound; from close to distant and everything in between. Either the "mono" or the "stereo pair" can be used as the base sound. Think about a mono capture with some extra space or a distant pair with added fulness.

Examples

For the first recording, I used a Neumann TLM 193 relatively close to the guitar, and a wide pair of DPA 4011As as room microphones.

In isolation, neither the Mono signal nor the AB pair sounds particularly great. The first is somewhat plain and too direct, while body and weight are missing from the AB pair. When mixing all three microphones, the combined sound gets defined and three-dimensional; thus more real.

I made another example of the same setup and the exact same distances, this time with an Austrian Audio OC818 in Cardioid for the Mono duties. The AB pair is still the DPA 4011A. If you have read my Austrian Audio OC818 review, you already know that I love their sound, and I wanted to hear how well they can mix with the DPA microphones.

Combining M/S and Room Microphones

A few months ago, I also experimented with combining an M/S pair of Neumann TLM 193 and AEA N8 up close and a stereo pair of Austrian Audio OC818s at some distance, you can hear the result in this recording of Bach's Cello Prelude no.2.

Some things to take care of

If you want to try the Three-microphone setup, it is important to listen to the recording as a whole before committing to any microphone position. The Mono microphone may be judged alone if you plan to use for the main sound, but don't make bold decisions without listening to the combined audio.

Potential phasing nightmares is one of the biggest drawbacks of this setup, so take extra care to eliminate any issue and check with a proper phase meter plugin regularly (read my article on the Three Most Essential Plugins for Classical Guitar).

Lastly, although the recording should be evaluated as a whole, the close and distant setups might need to be EQed separately. Nevertheless, you may apply a catholic EQ with basic filters and sculpturing.

Cheaper Alternatives

Line Audio CM3 - A budget SDC with an surprisingly good sound

Apart from the aforementioned combinations, any microphone could do a decent job. If you just starting and your budget is limited, buy the best large-diaphragm condenser you can afford and a pair of cheaper small-diaphragm condensers, like the Line Audio CM3/CM4 (read my comparison of the Line Audio CM3 and DPA 4011A).

Final thoughts

I've seen mostly AB, XY, ORTF and sometimes M/S setups explored by engineers and home recordists for the classical guitar. All of which can produce excellent recordings given the right circumstances. Yet, I find that with more elaborate techniques I can capture the instrument, at home or on location, with exceptional precision, without any disadvantages. Except maybe for needing more input channels, cables, stands, and more time for the setup.

A Three-Microphone setup can shine in a very wet hall, as it allows us to capture the body and definition of the instrument while including as much ambience as desired. In a home recording of the classical guitar, it offers great flexibility, if not to provide ambience, it combines the intimacy and fullness of a close pick-up with some extra depth provided by the spaced pair.

So, what do you think? Have you tried a three-microphone setup? Which microphones have you used?

6 Common Mistakes When Recording the Classical Guitar at Home

Part I - The room and the microphones

You just bought a couple of microphones and want to start recording your classical guitar at home; share your recordings with your friends, archive your performances, or start your career as a professional guitarist or recordist. Additionally, recording yourself will force you to look straight into your flaws, thus improving you as a player.

These past few months, I have received quite a few emails and taught several Skype sessions with the focus on recording classical guitars. There are a few mistakes that seem to be common, mistakes that we all do when we first start recording.

In this article, I discuss some of the flubs of the beginner recordist that have to do mainly with the microphones and the room.

You can also read the 6 Common Mistakes When Recording Classical Guitar at Home, Part II article, where I discuss about utilizing a proper signal chain and achieving satisfactory results in post-processing.

Mistake no.1 - Not spending enough time to study the room

Julian Bream - A Life on the Road (Book, 1982)

Every room is different, and If I had to take something out of the brilliant Julian Bream’s book "A Life on the Road" is how essential is to take the extra time to find the spot of where the guitar sounds the best in the room you are; the position in the room and the angle towards the sides are some of the things to consider.

Of course, Julian Bream mainly talks about performances, but the same logic applies to the recording aspect as well. The best sounding spot in the room will allow you to play more comfortably, thus you might sculpture a nicer sound of your guitar; and depending on the microphone technique you use, added ambience or the elimination of unwanted reflections will have an enormous impact on the final recording.

Usually, most of us sit where it is convenient and don't think much about positioning the microphones, as long as they are not in the way. Some others, they like symmetry and will position themselves or the microphones in the middle of a square or rectangular room; the worst sounding spot in a room like this, introducing a plethora of problems that are impossible to remove.

So, try a few different positions, angle the guitar towards one of the sidewalls, maybe sit a little closer to the back wall, to give some space and allow the guitar to project properly. Better yet, ask someone else to play the guitar, ask them to try a few different positions and observe how it affects the sound. Use your ears as if they were the microphones.

Mistake no.2 - Placing the microphones too far away from the guitar

Norbert' Kraft’s distant miking with a spaced pair of Neumann microphones

If you have ever watched any Naxos videos, you must have noticed Norbert Kraft's distant and wide miking. Similar techniques can be seen any many famous recordings. Getting influenced by professional recordists can be inspiring, but also equally misleading as the source material is very different. Techniques that can be excellent in a church, large halls, or even a well-treated studio never apply to the smaller room reality of the home recordist.

By following such techniques you might end up placing the microphone(s) closer to the front wall than the guitar. Even when the microphone(s) are close to equal in distance, it is possible to end up with an overly diffused and roomy sound; as a result, the sound of the small room will be forever embedded in your recording. Getting too wide will also be a problem if the room is not wide enough. Also, the guitar is a small instrument and rarely benefits from a very wide pick up. Therefore, try moving the microphones closer to the guitar but not too close.

Mistake no.3 - Placing the microphones too close to the guitar

Pat Metheny - nylon string recording; don’t try this at home!

After failing with the "church-technique", many of us want to get rid of the small room sound altogether, we have amazing reverb plugins anyway, and start positioning the microphone(s) very close to the guitar, I mean really close. To a similar erroneously path can arrive those with an acoustic guitar background or those who have witnessed some terrible close-miking examples in even famous recordings.

The problem is actually... threefold:

Firstly, by placing the microphones too close, finger and other mechanical noises will creep in, resulting in an annoying and unattractive recording. You may start cutting high frequencies to remove some of those artefacts but sooner or later you'll end up with an immensely dull recording.

Then, most of us usually start with directional microphones, those exhibit a pronounced low-end frequency response due to the proximity effect. One can balance the unwanted boost with careful EQ-ing, but beginner recordists won't have the skills for that. The low-frequency boost combined with the need to cut high-end information will produce an unbalanced imitation of a classical guitar.

Furthermore, the classical guitar is a complex instrument; every part of the top projects different frequencies that they all combine at some point to create a cohesive and rich sound. Normally this point is around the length of the soundboard, about 50cm, that should be the limit of how close you can get with the microphone(s): Greater distance is preferable if the room allows, but, never record classical guitar closer than 50cm.

Remember, classical guitar needs space!

Mistake no.4 - Not experimenting with microphone height, angle and techniques

Placing the microphone(s) at the height of the guitar is a decent place to start, but as microphone height and angle influences so much the overall character of the recording, ignoring other possibilities will frustrate you as you will have to fight with post-processing to get the desired result. It is preferable to spend the extra time and set up the microphone(s) correctly.

Normally, as classical guitarists learn to project their sound slightly upwards, the further away you place the microphone(s), the higher they should be positioned. And, by allowing the microphone(s) to face a bit downwards, so to be on-axis with the guitar, you can achieve a realistic and full-range recording with great definition. This technique will capture what is usually called the "audience perspective".

If you notice that the guitar, guitarist or microphones to sound a little sharp, you can angle the microphones slightly off-axis to reach a smoother treble response.

In the case of spaced pairs, it is not uncommon to point the microphones somewhat outwards so that they are not parallel to each other. But in a small room, and at greater distances, additional room reflections will soak into the recording. Thus, I've found that is more desirable to point the microphones slightly inwards or a little higher to achieve a mildly off-axis response but with less "room" in the recording.

For those who pursue an intimate and fuller sound, with a tame high-end and less room, what is called the "player's perspective"; miking the guitar a little closer and with the microphone(s) lower is a good place to start. Avoid placing any microphone opposite of the soundhole, otherwise, the recording will become boomy. For an even fuller sound, place the microphone(s) lower yet, and point them upwards.

The discussion about miking techniques is a complicated one and deserves its own article(s), but until I write it, these ideas should get you a bit more involved.

Mistake no.5 - Not checking for phase problems in stereo recordings

The 2CAudio Vector plugin includes a phase meter and its free!

The classical guitar should be recorded in stereo. Either a pair of spaced condensers or one of the several other stereo setups will do. Except for the coincident microphone techniques, like M/S Stereo and X/Y, any technique that involves two or more spaced microphones, can potentially become a phase nightmare.

Phasing has a noticeable influence on the sound quality of your recording, as due to cancellations and comb filtering it can potentially leave your recorded guitar sound thin and weak. Be sure to check for phasing problems with a proper plugin (I use the 2CAudio Vector, it has a phase meter, plus some other welcome features and its free), adjust the microphones until you minimize phase - everything higher than 80% on the meter is acceptable. You can still compensate for phasing during mixing, but it’s always better to take care of it beforehand.

Mistake no.6 - Thinking that more expensive microphones or preamps will fix all problems

Shopping for new microphones, interfaces and other toys... I mean tools... is fun; a big chunk of writings on this site is about reviewing and comparing recording equipment. But, at this age, pretty decent recordings can be made with a reasonable budget. So blaming the gear is only an excuse for not willing to go the hard way.

Refrigerator racks with outboard equipment can be fun, but we can do a lot with a couple of decent microphones and an audio interface

I'm not arguing that equipment doesn't matter; it does. It just not going to substitute for bad microphone positioning, an unsuitable room or not refined guitar technique. Contrary, more accurate and detailed microphones will accentuate any of the problems that are present.

Learning how to use what you've got, experiment with various microphone techniques and positions; take steps to adjust your room for a better sound. And why not, maybe spend some time practising and try to be well-rehearsed before you press the record button. These are some basic actions to take that can drastically improve your recordings in a meaningful way.

Closing thoughts

Mistakes are part of the learning process; don't be afraid to make them, and don't hesitate to experiment. After all, recording is a journey, and the process of trying things can be a valuable lesson in becoming a more accomplished recordist.

I hope that this article might encourage you to try out different microphone positions, learn and improve your room. Optimistically, the information provided here will guide you to make better recordings.